In previous articles, we have analyzed how the pandemic has increased the chances of human rights violations to occur. As an example, we can mention the violation of the rights to privacy and to freedom of expression through mass surveillance carried out with the help of new intrusive technologies. In this article, however, we will focus on how technology can be used to protect human rights and confront the historical pandemic of gender-based violence.

Prior to the existence of COVID-19 and the subsequent declaration of a pandemic by the WHO, gender-based violence had already been declared a ‘shadow pandemic’ by the UN in November 2016. According to UN Women, “one in three women worldwide experience physical or sexual violence mostly by an intimate partner”. Along the same lines, the WHO had pointed out already in 1997 that “among women aged 15–44, acts of violence cause more death and disability than cancer, malaria, traffic accidents and war combined”1. Furthermore, the Executive Director of UN Women reported in a statement dated April 6, 2020 that “[i]n the previous 12 months, 243 million women and girls (aged 15-49) across the world have been subjected to sexual or physical violence by an intimate partner.“

Although some efforts have been made by certain governments, such as the enactment of specific laws and targeted public policies, the seriousness of the situation has not been acknowledged in the same way as the COVID-19 pandemic, neither by the states nor by the citizens in general. Proof of this is that there has never been a general state of alarm regarding the deaths and violence suffered by women, nor a permanent vigil on the subject, as is the case with Covid-19.

Gender-based violence has increased during the pandemic

Gender-based violence has increased under the situation of home confinement resulting from the lockdowns established globally in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In this regard, the regular concept of a ‘safe home’ gives a clear example of the difference in how women inhabit spaces. A home is usually presented as a safe haven and the current context has further strengthened this concept, since the first recommended protection measure against COVID-19 is to stay indoors. In this way, our own house is represented as an element of protection; however, for many women, the house can represent the exact opposite: it can be a danger to their physical and/or psychological integrity, and even to their lives. This is due to the fact, mentioned above, that gender-based attacks come in most cases from the victim’s partner.

This means that a woman who already suffered violence from her partner is now locked up almost 24/7 with her attacker. Before the pandemic, perhaps she had some opportunity to seek support or psychological help, or to file a complaint while the partner or herself were at work or had other activities. But now with the pandemic, isolation and control (pillars of the cycle of violence) intensify, making it impossible for women to turn to the trusted people or resources that could help them.

Moreover, the current circumstances may generate some kind of disruption in public services like police, justice or social services. Such disruption may also jeopardize the care and support that survivors need, such as clinical treatment for rape victims, or psychosocial and mental health support. In addition, the impunity of the aggressors is enhanced.

In the statement mentioned above, Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, Executive Director of UN Women, noted that with the advance of the covid-19 pandemic, the number of incidents related to physical and sexual violence are likely to grow, with multiple effects on the well-being of women, their sexual and reproductive health, their mental health, and their ability to lead and participate in the recovery of our societies and economies.

According to a report by UNFPA dated April 27, 2020, on the “Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Planning and Ending Gender-based Violence, Female Genital Mutilation and Child Marriage”, Covid-19 prevention and mitigation measures, such as quarantine, social isolation and mobility restrictions, will result in an increase in violence against women and girls. Additionally, these measures can have a negative impact in their mental health, since being locked in with their aggressors can generate anxiety, depression and long-term impacts on their development.

Regarding the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for 2030, the UNFPA report warns that, as a consequence of the pandemic, efforts to advance towards SDG 5 (Gender Equality) could be threatened, especially in relation to gender-based violence and women’s sexual and reproductive health. On violence, it states that the COVID-19 pandemic “is likely to undermine efforts to end gender-based violence through two pathways: reducing prevention and protection efforts, social services and care [and] increasing the incidence of violence”. Regarding sexual and reproductive health, it warns that the number of unintended pregnancies “will increase as the lockdown continues and services disruptions are extended.”

According to their estimations, “for every 3 months the lockdown continues, assuming high levels of disruption, up to 2 million additional women may be unable to use modern contraceptives”, and add that “if the lockdown continues for 6 months and there are major service disruptions due to COVID-19, an additional 7 million unintended pregnancies are expected to occur.”

What about Paraguay?

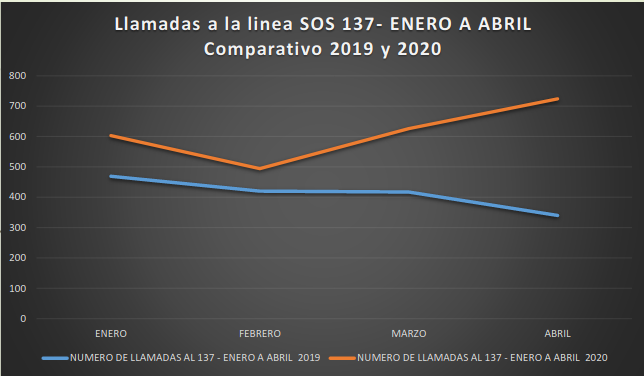

In Paraguay, at the beginning of the mandatory quarantine, the Public Ministry reported an average of 80 new cases of domestic violence per day, and the Judiciary found 118 cases of family violence “as a punishable act” committed from March 12 to 27. At the same time, the Ministry of Women published a report on the incidence of violence in times of covid 19, dated June 2, 2020, presenting comparative tables of calls to the SOS Women line 137, before and during the quarantine, where it can be observed that the number of calls during March and April (months of confinement) was much higher than that of February. When looking at the table comparing the current year with 2019, it can be observed that the increase occurred precisely in the quarantine period, going up by 78%. In March 2019, the Ministry of Women reported 417 calls to SOS 137 denouncing attacks, while in March 2020 the number of calls increased to 626. As for comparing the month of April, in 2019 there were 340 calls and in 2020 the number increased to 724.

How can technology help?

As mentioned before, for women suffering domestic violence, the fact of being in quarantine implies either being confined without the opportunity to leave their homes, or at least being subject to movement restrictions, which increases the possibility for the aggressor to impose his control and at the same time increases the victim’s isolation. In those cases, having a mobile device becomes key to be able to communicate with the outside world, be it to get in contact with support networks or to file a complaint. Nonetheless, just having the device does not mean that it is safe: your cellphone can also be controlled.

It is not news that aggressors also make use of the latest developments of technology to enforce their control. They may demand to have the victims’ passwords, to check their messages and photos, to use the devices’ GPS to monitor where the person is at all times, to name but a few of many possible examples. This being said, there are however mechanisms that allow us to harness the potential that these tools have as a means of empowerment and liberation.

The organization Derechos Digitales translated into Spanish a MariaLab guide on digital care during the pandemic for women who are going through situations of violence, entitled “Care during the pandemic: how to denounce domestic violence”2. In this guide, they provide a series of extremely useful tips to ensure that these devices can help to protect women.

We highlight below some of those tips:

How to find out if your aggressor is monitoring you

First of all, you have to ask yourself if the mobile phone was a gift from the aggressor, if the operating system or apps were set up or modified by him and if he had (or has) access to your phone for considerable periods of time. If the answer to any of these questions is yes, you should check your cellphone settings. There are some ways to do this:

1. Scan your cellphone for spyware: check if your cellphone has been placed in ROOT mode. Spy apps use this mode to monitor your actions without you noticing. That is, by using a spy app someone can access your entire cellphone: chats, pictures, location, calls, etc. To verify the phone’s mode, we recommend that you download the app Root Verifier (for Android) and perform this verification.

2. Make sure you have access to your Google or iCloud account on your phone and, if possible, change the password.

3. Check if there are “Find my Phone” apps installed anywhere on your cellphone. They are usually found among the cellphone’s remote management apps (Samsung, Nokia, LG). If you find one of these apps, check the account used to log into it and, if you do not recognize the account, deactivate the app, since it could reveal your real-time and historic location to the person who has access to the account. If you do not know how to disable applications, check this link for Android, or this link for iPhone.

4. Check if among the apps installed on your cellphone there are any with “Superuser” permissions. Applications having this permission have much more control than others, and they may be spyware or a virus. Here is a link on how to revoke app permissions.

How to make your phone more secure

- Set a password to lock your phone, preferably an alphanumeric password (combining letters and numbers). Here, a step by step on how to do it on Android.

- Check the apps installed on your cellphone. Go to Settings > Applications and see what you can find out about what each does. If you find an app that you do not use or do not know what it is, look for more information about it on the internet. If it is not a system application, uninstall the app. See here, how to delete or disable apps on Android.

- In case you are not able to set a password or have privacy on your cellphone, due to pressure from the aggressor, it is possible to install a password application to block other applications and simulate an error. This app mimics a problem on the cellphone when a person tries to access other apps without a password. For this, we recommend AppLock.

- In case your aggressor checks your messages on the cellphone, we recommend erasing the chat message history and agreeing to basic communication codes with your support networks. Also remember that your internet browsing search history is recorded on your cellphone. For added protection delete those records as well. To delete WhatsApp media files, go to the picture and video Gallery on your cellphone, then select and delete the folders “WhatsApp Images” and “WhatsApp Videos”. To delete your Chrome browsing history, follow the steps given in this link.

How to register and save images safely

- An audio recording, a picture, a video or even the screenshot of a chat conversation can become important evidence to denounce the aggressor, but before gathering any potential evidence think about your safety. If you do not feel safe, do not keep a record.

- Cellphones can be used to record audio, videos, photos and texts, and there are many apps that can help with that registration. When you use them, remember to register the place, date and time of each incident. That information will be useful for the complaint. To record and protect information on your cellphone, we recommend using the following apps that can hide photos, videos and other files of your choice:

- For Android: Andrognito

- For iPhone: SecurePad

Together we take care of each other

Do you know any organization or collective that works on the subject, or did you find any additional related resources or materials that you would like to suggest?

Share it in your comments or write to us at our contact form.

Lastly, we would like to recall that in many countries you can have access to helplines 24 hours a day, every day. These helplines offer guidance and support to female victims and assist people who have knowledge of cases of gender-based violence. Here you have a list of Domestic violence hotlines in some countries, or you can select your region to find hotlines in other countries following this link.

Notas:

- Quoted from UNIFEM, Violence against Women Worldwide (Fact Sheet): https://www.womensaid.ie/assets/files/pdf/unifem_vaw_factsheet.pdf

- Original in Portuguese: MariaLab, Cuidados durante a pandemia: como denunciar uma violência doméstica?; Spanish translation: Derechos Digitales, Cuidados durante la pandemia: ¿cómo denunciar la violencia doméstica?

Worrisome regulation on disinformation in times of COVID19

Worrisome regulation on disinformation in times of COVID19  Access to Knowledge Coalition

Access to Knowledge Coalition