TEDIC has launched a new study called “Propaganda in Social Networks Exists: Monitoring electoral spending on Facebook Ads in the Municipal Elections of 2021 in Asunción,” with the support of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). TEDIC has been carrying out advocacy actions for years in order to achieve greater transparency and scrutiny over the electronic voting system in Paraguay.

This study analyzes what took place during the municipal elections of 2021 in the city of Asunción, Paraguay. It seeks to expose the legal framework, the electoral results and the development of an exploratory analysis to offer recommendations on resources invested in electoral propaganda on Facebook published during 2021, from official pages of candidates for mayor and the main council positions that were elected during the period mentioned.

In order to achieve the proposed objectives, our study uses public data from Facebook, complemented with datasets and reports on electoral spending published by the Superior Tribunal of Electoral Justice (TSJE; for its name in Spanish) of Paraguay.

Among the main findings, our study revealed:

Social Media:

- Social Networks are not regulated by electoral legislation. There are debates on the ways in which they can be regulated. A bill that recognized social networks as spaces for the dissemination of electoral propaganda, presented in 2015, did not prosper.

- Social networks are not significant in terms of spending volume. According to data from Semillas para la Democracia, Gs. 5,964,442,800 (USD 864,412) was allocated to propaganda on social media platforms and public roads in Asunción. However, the total expenditure on ads distributed on Facebook and its advertising resources, considering only what was executed by candidates for mayor and councilors elected in the city of Asuncion, reached Gs. 177,926,367 (USD 25,7831), meaning comparatively, only 2.94% of the total amount invested in other information channels.

- According to Facebook, the candidates for mayor of the city of Asunción spent only Gs. 24,696,600 in advertising on this platform. The mayoral candidate who invested the most was Johanna Ortega (APT), with Gs. 9,843,230, and the one who invested the least was Diego Oliver (PCN), with Gs. 29,923.

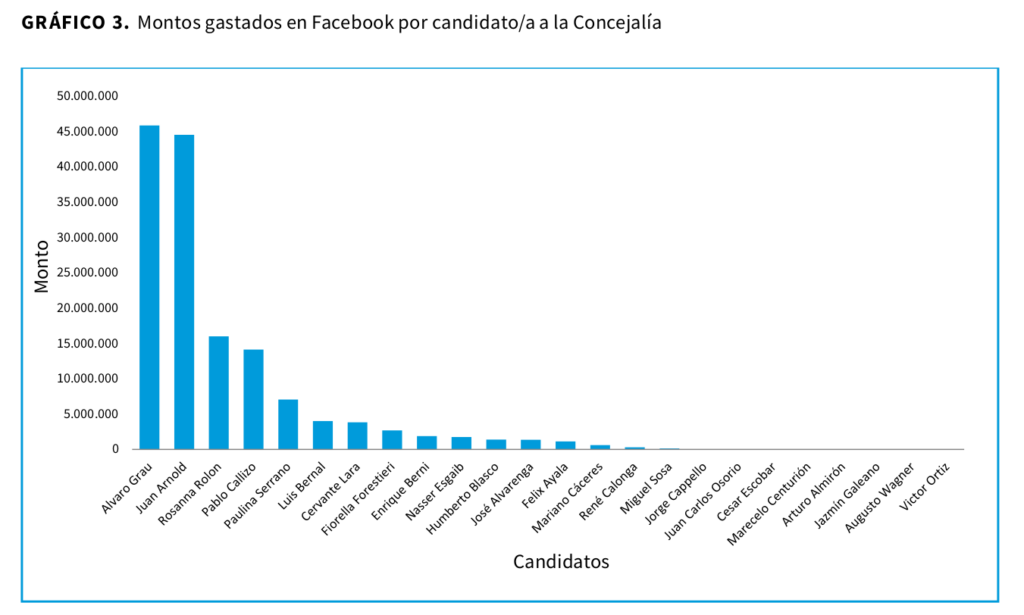

- Councilman Álvaro Grau (PPQ) was the candidate for the Municipal Council of Asunción who has spent the most on this social network with spending of Gs. 45,866,090, well above Miguel Sosa and René Calonga, both from the ANR, who spent the least amount recorded by the platform, with an expenditure of Gs. 300,117 and Gs. 134,992 respectively.

- Mayoral Candidate Eduardo Nakayama (JA) ran the most costly ads on this social media platform, followed by his competitor Johanna Ortega (APT). Óscar Rodríguez (ANR) takes the second to last place, followed by Diego Oliver (PCN).

- On the basis of a formula that quantifies the investment in networks versus the number of votes received, called “Vote Value in Asunción,” it revealed that Carlos Eduardo Ruiz (PMPP) had the highest vote cost as Gs. 3,450, compared to Óscar Rodríguez, at Gs. 5 per vote. This calculation, although not representing a direct correlation, helps to estimate the existing inequalities in the cost of the campaign between small or emerging spaces versus traditional electoral structures.

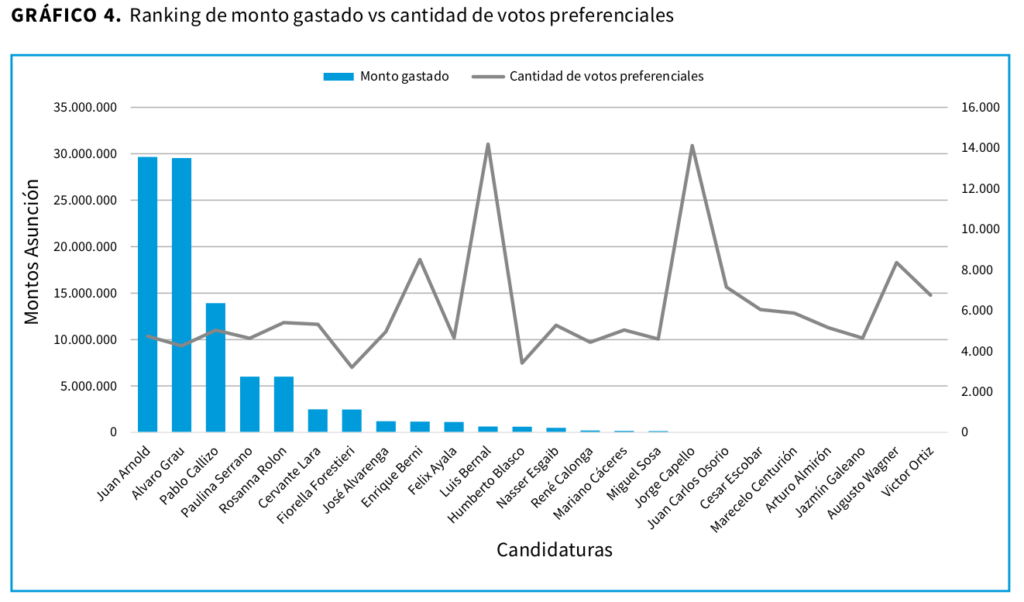

- A comparison between the total amount spent in Asunción by each candidate versus the number of preferential votes obtained by each councilor suggests that there is not a direct expenditure/vote relationship and that each case should be analyzed individually.

- There were candidates who, without significant investment in networks, had considerable electoral peaks, such as Luis Bernal (ANR), Enrique Berni (ANR), Jorge “Turi” Capello (ANR) or Augusto Wagner (PLRA). They demonstrated their political strength through propaganda in other channels.

National Observatory of Political Financing (ONAFIP):

- The ONAFIP does not disaggregate the information on advertising and electoral expenses in greater detail, for example, according to the platform or medium to which it is destined.

- Of the seven candidates running for office for the city of Asunció, only the current mayor, Óscar Rodríguez (ANR), declared having spent on electoral propaganda and advertising the total sum of Gs. 67,070,000, distributed between two service providers: Germán Martinez y Asociados and M.G.M S.A. Imagen y Publicidad (TSJE, 2022). Media monitoring by Semillas por la Democracia identified a 24 times higher expenditure, estimated at USD 235,688 and equivalent to Gs. 1,626,247,000 (Semillas para la Democracia, 2022).

- Among the other candidates, Johanna Ortega (APT), Eduardo Nakayama (JA), Luis Narvaja (CNFG), and Carlos Eduardo Ruiz (PMPP) presented their declarations with amounts in zero. On the other hand, the declarations of electoral expenses of Enrique Ferreira (PNU) and Diego Oliver (PCN) have not been published.

- In candidacies for the Municipal Board of Asunción, the total investment allocated to propaganda and advertising by all candidates reached the total sum of Gs. 403,051,985 (USD 58,405) (TSJE, 2022).

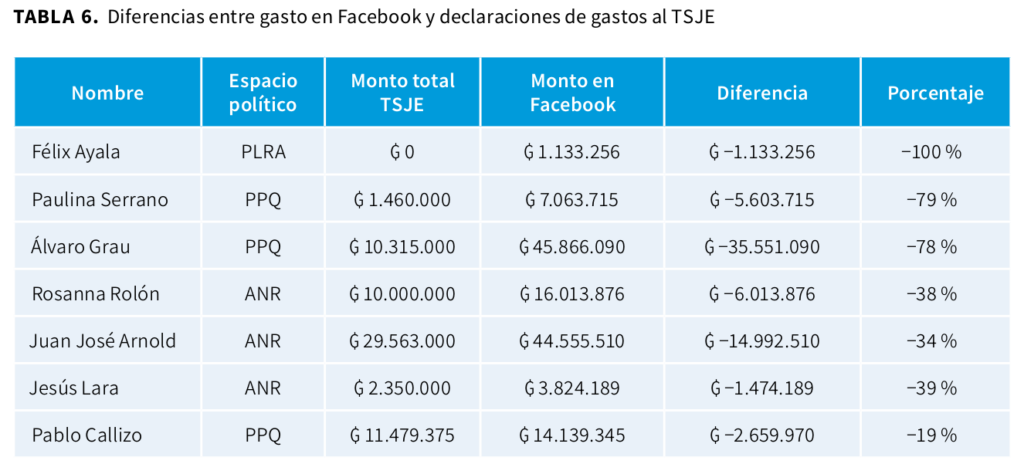

- When comparing the declarations of the expenses submitted to the TSJE and the estimates of advertising costs on Facebook, a significant underreporting is evidenced, observed in at least seven of the candidacies with elected seats. The candidacies of Álvaro Grau, Paulina Serrano and Pablo Callizo of PPQ reflect an under-report ranging from -19 to -79%. In the ANR, Juan José Arnold Rosanna Rolón and Jesús Lara range from -34 to -39% and Félix Ayala of the PLRA with a -100% of underreporting by declaring to the TSJE not to have incurred in expenses.

Conclusions and recommendations:

- Articulation among diverse actors is required in order to promote proposals for changes to the platforms and the willingness of these companies, as Meta, to incorporate the recommendation that come from electoral management bodies as well as from civil society and organized academia.

- Facebook categorizes in its “library of ads” those ads of a political nature. However, unlike the global north, in Paraguay they only only categorize those in the aforementioned tag, and not other topics such as “housing,” “credit,” or “employment.” If quality standards are the subject of discussion in other part of the world, they should also be mechanisms applied in countries of the global south.

- The findings of this research open a reflective path to which the majority of actors interested in strengthening electoral processes should be part of. In this author’s opinion, the electoral expenditure reports seem to be merely declarative, without legal consequences at the moment of not complying with the norms and with great inconsistencies between what is presented and what has actually been invested. It is urgent and necessary that the existing technological resources be adjusted to optimize the incorporation of a Human Rights perspective, the principles of democracy and transparency, in the face of its threatening darkness, by means of ill-gotten money and weak control mechanisms for electoral financing.

- This report shows that the four women joining the Municipal Board allocated between 11 to 110 times more financial resource that the councilor with the highest investment in electoral propaganda. This is also reflected in social media platforms.

- It is necessary to make the advertising cost policy transparent and discuss the incorporation of spaces reserved for advertisement and propaganda in social media platforms. The role of platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and other social networks as spaces to be occupied during electoral campaigns should also be a topic of conversation.

- It remains to be clearly defined whether they should, in some way, be legally assimilated as Mass Media (MMC) or whether they should be governed by a different regulatory framework, given that, like traditional media, they charge fees for video reproduction, image and text broadcasting or occupation of the reserved advertising spectrum.

- It is necessary that social media companies fully disclose the information on the exact amounts executed and the details of the segmentation applied, such as gender, age, socioeconomic level, use of database, among others, which could mean non-consensual use of data or violation of rights, intentional targeting of campaigns with discriminatory criteria or use of resource that do not math those declared in official documents. For this purpose, the TSJE could advance in official contacts and possible agreements with the platforms.

- Regarding language policies, it is necessary that the exportable data for analysis use categories and descriptions in the official language of the country consulted. The data provided by Facebook, is available in English, not in Spanish or Guarani, making access even more difficult for the local population.

- It is necessary to advance in standards on monitoring electoral spending in social networks, especially as a practice to be incorporated in electoral bodies. There are already interesting experiences in the region, for instance Mexico or Chile, which could be considered as a starting point for local approaches.

TEDIC is committed to continue to carry out a series of reports, observation, and advocacy actions, in order to generate the greatest understand possible of the impact of ICTs in the electoral process. We invite you to stay tuned to our social networks to access this information.

Click here to download the entire report!

1 Semillas para la Democracia. (2022). ¿Cuánto cuestan las elecciones? Monitoreo del gasto en campaña electoral de las Elecciones Municipales 2021. https://www.semillas.org.py/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Informe-de-Monitoreo-de-gastos-electorales_octubre-2021_SPD.pdf

Online course: Free and safe on the Internet

Online course: Free and safe on the Internet  [Research Release] Understanding the National Ticketing System: An exploratory study

[Research Release] Understanding the National Ticketing System: An exploratory study