In Paraguay, the use of biometric surveillance technologies is expanding without public knowledge, debate, or legal frameworks to ensure the protection of our fundamental rights. Facial recognition cameras are already installed in streets, football stadiums, public offices, and institutional buildings, capturing sensitive data from thousands of people every day. But who controls this technology? What criteria are used to activate these cameras? What do public institutions do with the images and biometric data they collect?

A new investigation by TEDIC —based on freedom of information requests, strategic litigation, and analysis of official documents— reveals an alarming reality: the Paraguayan State has been implementing facial recognition technology in an opaque manner, without specific regulation, misusing public funds, and violating basic rights such as privacy, freedom of movement, and the presumption of innocence.

Since when have we been watched?

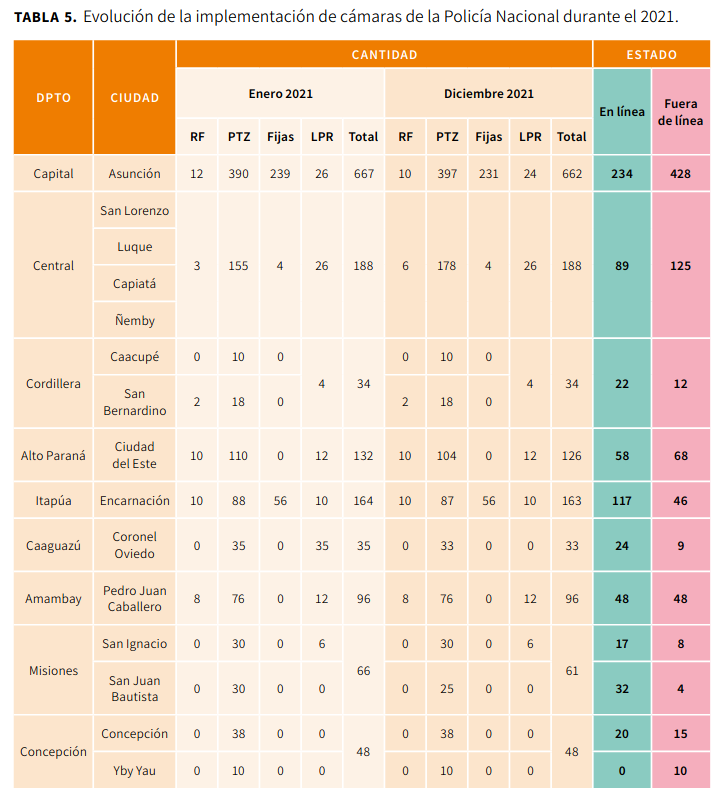

The implementation of facial recognition cameras began in 2018, when the National Police announced the acquisition of 154 cameras, 44 of which included this technology. Since then, their use has expanded through multiple purchases made by the Ministry of the Interior, the National Telecommunications Commission (CONATEL), municipalities, and other public entities. In our new investigation, we point out how these acquisitions were not only difficult to track due to the way the bids were classified, but in many cases were disguised as purchases of “office” or “educational” equipment, making proper oversight nearly impossible.

Who bought these cameras?

Through the analysis of public information and official documents, we identified at least 13 public institutions that acknowledged possessing facial recognition technology, including:

• National Administration of Navigation and Ports (ANNP)

• National Directorate of Migration

• Itapúa Governorship

• Municipality of Paraguarí

• Chamber of Senators

• National Directorate of Civil Aeronautics (DINAC)

Additionally, the governorships of Presidente Hayes, Boquerón, and Caaguazú, as well as the Ministry of Finance, SENAD, the Ministry of Justice, and the Binational Entity Yacyretá also acquired cameras connected to the 911 System.

Public Funds diverted

One of the most alarming findings of this investigation is the use of the Universal Service Fund (USF) —administered by CONATEL— to finance video surveillance technologies, including facial recognition. This fund was created with a clear purpose: to guarantee universal access to telecommunications services, prioritizing rural communities, Indigenous peoples, and historically excluded sectors with limited access to the internet and phone services.

According to both national and international regulations, USF resources must be allocated to projects that promote digital inclusion, connectivity in schools, health centers, and public spaces, affordable access to devices and services, and the development of digital skills in vulnerable communities. In other words, it has a social mission aimed at closing the digital divide from a rights-based approach.

However, between 2011 and 2022, CONATEL awarded 27 contracts through the USF. Starting in 2016, a troubling shift in the use of these funds became evident: they began to be used to purchase video surveillance cameras—many of them equipped with facial recognition technology—instead of being allocated to ensure internet access in areas with low or no connectivity.

This diversion not only goes against the original purpose of the fund but was carried out without transparency mechanisms, public consultation, or impact assessments, and without meeting human rights standards that should guide any state technology policy.

TEDIC raised the alarm about this issue in 2018, which sparked international concern: both the Alliance for Affordable Internet and the Internet Society warned that this practice violates the principle of proper use of public funds and sets a harmful precedent in the region—showing how governments may use funds intended to guarantee rights to instead deploy surveillance infrastructure. In concrete terms, what we see is a discretionary and potentially improper use of public resources which, instead of benefiting vulnerable populations, ends up expanding the State’s capacity to surveil, monitor, and profile citizens without regulation, without accountability, and without safeguards.

Strategic Litigation to Demand Transparency

Since 2018, we have been driving strategic litigation against the Paraguayan State to demand access to public information regarding the implementation of these technologies. In total, three legal actions have been initiated:

- In 2018, an injunction against the Ministry of the Interior was rejected on the grounds of “national security,” without any concrete legal justification. This ruling legitimized state opacity and reproduced authoritarian logics reminiscent of the country’s dictatorial past.

• In 2023, two new injunctions again sought to obtain public information about the use of facial recognition. Both were also met with institutional and judicial refusals.

These cases reveal how state surveillance is advancing outside the rule of law, without accountability, and with a worrying normalization of secrecy.

Minimal results, maximum risks

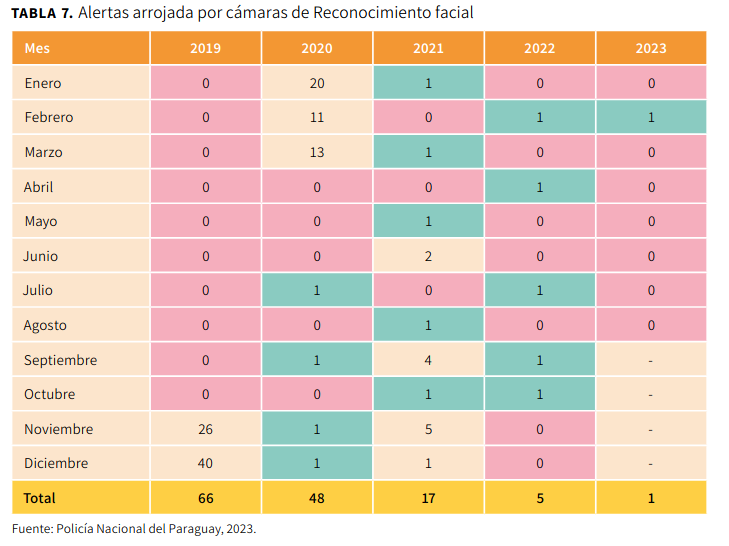

Records from the National Police themselves contradict the official narrative that justifies these technologies based on their “security effectiveness.” Between 2019 and 2023, facial recognition systems issued only 137 alerts over four years—just one of them in 2023.

Faced with such marginal outcomes, the human rights cost is immense: mass surveillance, discrimination, false positives, and the creation of a digital ecosystem that criminalizes simply being present in public space.

A State without a Data Protection Law

Paraguay still does not have a personal data protection law. This means there is no legal framework to limit or regulate how people’s biometric data is collected, stored, or processed.

Despite this, in 2024 Congress passed the Sports Violence Law, which authorizes the use of facial recognition in football stadiums—without adequate safeguards for rights protection or citizen oversight mechanisms. This happened after the Ministry of the Interior and the Paraguayan Football Association had already signed agreements to install these cameras.

What do we propose from TEDIC?

In light of this scenario, our investigation concludes with three urgent calls to action:

- Immediately suspend the use of facial recognition technologies until a robust, human rights-based personal data protection law is in place.

- Investigate the misuse of public funds—especially those from the Universal Service Fund (USF)—and sanction their use for surveillance.

- Guarantee public access to all contracts, agreements, and procurement processes related to biometric surveillance technologies.

Because your face is not just another data point. It’s your identity. It’s irreplaceable. And it must be protected. You can download the full investigation by clicking this link. You can also join our campaigns #MyDataMyRights and #NotWithMyFace on social media.

[Research] Technology-facilitated gender-based violence against women politicians in Paraguay

[Research] Technology-facilitated gender-based violence against women politicians in Paraguay  Starlink in Paraguay: are there risks or concerns about this technology?

Starlink in Paraguay: are there risks or concerns about this technology?