Platform work in Paraguay continues to be a changing and evolving reality. Thus, the generation of information from different stakeholders and disciplines is a necessary step towards understanding the implications of the development of this economy in the country.

Since 2021, TEDIC is a member of the Fairwork network, an action-research project that aims to shed light on how these technological changes affect working conditions around the world by evaluating platforms through principles of fair work that were developed collaboratively amongst different stakeholders. Part of the work of this network is evaluating the working conditions of location-based platforms via a ranking report that is based on its five principles of fair work: Fair pay, fair conditions, fair contracts, fair management and fair representation.

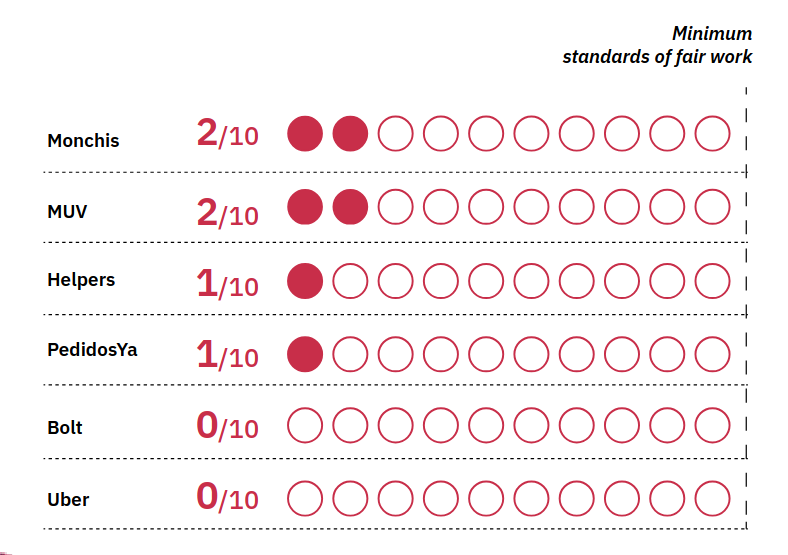

The Fairwork report, which had its first edition in 2022 in Paraguay, evaluated six relevant platforms: Uber, Bolt, MUV, Pedidos Ya, Monchis and InDriver. The six platforms mentioned are national and foreign companies and belong to the passenger transport and product delivery sector. The report highlighted a number of challenges. The scores were very low, indicating that basic labour standards for platform workers in Paraguay are still far from being met. The first Fairwork Paraguay report found no clear evidence that any platform ensures workers earn at least the national minimum wage after costs. It also found no sufficient evidence that platforms take steps to reduce health and safety risks or provide social protection. Finally, it could not confirm the existence of formal policies showing that platforms are willing to recognise and negotiate with workers’ organisations or trade unions.

After three years since its first publication, TEDIC is pleased to officially launch the second report of the Fairwork Paraguay study. In the three years since the first report, notable shifts in the platform economy have occurred. For example, the transport platform InDriver has ceased its operations in Paraguay, illustrating the volatility and transience of platform-based work.

The current review focuses on six prominent platforms: Bolt, Uber, and Muv, which provide passenger transport, and PedidosYa and Monchis, which deliver goods. These platforms are the most visible in the national market. Recognising the continued expansion of platform work into new sectors, the report also evaluates the domestic work platform, Helpers. This attention to the domestic care sector is part of a concerted effort across Fairwork reports in eight Latin American countries that were simultaneously launched at the beginning of January of this year, including Paraguay, to shed light in the expansion of platform work in different fields of the economy. It is important to highlight that this work is possible thanks to the support of the Internet Society Foundation.

Key findings

Fair Pay:

● The collected evidence did not allow us to confirm that the workers of all platforms assessed receive either a guaranteed minimum wage or a living wage1 after accounting for work-related expenses. Although some workers reported relatively high gross earnings, these figures are predominantly linked to extenuating working hours for transporting passengers or delivering goods. While the dynamic in the domestic care sector is different, and not associated with a high number of hours of work, it was still not possible to award points to any platform as none of the two thresholds could be shown to have been met.

Fair Conditions:

● The available evidence did not allow us to confirm that any platforms implement substantial measures to address task-specific risks or provide a safety net equivalent to social security. While certain platforms offer some form of insurance or accident protection, access to these benefits often requires workers to pay daily fees, whereas in other cases, platforms absorb these costs themselves.

● Overall, most platforms could not evidence that they provide safety nets or protections equivalent to social security, and it was not possible to confirm that all platforms ensure access to safety training to all workers on an equal basis. It was possible to evidence that Helpers provides comprehensive social security coverage for all workers, a practice that will be highlighted later in this report. Therefore, we could not award points for the six platforms for each of the two thresholds.

Fair Contracts:

● Four platforms could evidence that they provide Terms and Conditions (T&C) to regulate their relationship with platform workers, while two provide contracts. For this assessment cycle, it can be confirmed that three of the six evaluated platforms subject themselves to the local jurisdiction or even establish a legal entity in the country, guarantee ongoing access to contractual documents, and explicitly reference data protection provisions. Thus, MUV, Monchis and PedidosYa were awarded a point for the first threshold of the principle.

● Based on the available information, it was not possible to award a point for the second threshold to any of the platforms. The workers we interviewed predominantly indicated that they are not notified of changes with reasonable notice periods. Furthermore, a review of contracts and terms and conditions obtained from workers could not confirm that platforms do not include clauses that restrict or exclude their own liability.

Fair Management:

● On a positive note, the collected evidence suggests that workers across all platforms do not appear to face barriers when raising concerns or appealing platform decisions. Nonetheless, most of the six platforms principally rely on automated systems for handling worker enquiries, which workers often described as insufficient for effectively resolving issues. In several cases, workers reported that visiting platform offices in person—where available—remained the only viable means to address certain concerns.

● It was possible to confirm that three platforms ensure communication channels that are consistently accessible and that involve human interaction. Consequently, three platforms (Muv, Monchis and Helpers) were awarded the first point under this principle. In the case of Helpers, due to its smaller size, problem resolution was shown to involve engagement even with senior managers for trouble shooting. No platforms received the second point, as it was not possible to confirm the existence of comprehensive anti-discrimination policies for workers nor established policies to promote diversity and inclusion.

Fair Representation:

● It was not possible to confirm the existence of public commitments from all six platforms to engage with organised groups of workers, or to identify mechanisms designed to facilitate collective expression of workers’ voice. While there is evidence provided in some testimonies pointing to limited engagement between some platforms and organised groups of workers within the transportation sector, such interactions remain isolated and have not received formal or public recognition from the platforms involved. Thus, no platform was awarded with any of the two points for this principle.

Moreover, as a further contribution to the development of the principles, and as part of a concerted effort across all eight countries that applied the Fairwork methodology in this cycle, particular attention was paid to regulatory issues. A table summarising the main ongoing regulatory debates, as well as regulations already in place or about to be implemented in all eight countries, is included in both the Fairwork Paraguay report and the other published reports.

To access the full report and a detailed explanation of each of the points, click here.

Moving forward

Three years after the publication of the Fairwork 2022 Paraguay report, it is evident that the establishment of digital labour platforms in Paraguay is robust. While public and centralised information is scarce, information published by a number of institutions indicates a consolidation of platform work in the country. From public policy reports demonstrating that the Bolt platform supports a labour force of approximately 20,000 workers, alongside government tax records confirming that PedidosYa ranks among the top 500 taxpayers with substantial indirect tax contributions, there is clear evidence of the extensive reliance on platform-based employment.

These findings underscore the necessity for a comprehensive analysis of platform work within the country—particularly given that a more just platform economy is still proving elusive. Protests of platform workers in response to arbitrary fee increases without due notice, as well as mobilizations in response to killings of platform workers are indication of lack of basic security and stability guarantees for platform workers in Paraguay. Moreover, there is a gendered dimension of platform work that exposes women workers to issues of sexual harassment, which has even led to situations where people have taken justice into their own hands due to a lack of support from platforms to identify perpetrators and block them accordingly.

Thus, TEDIC, through its Fairwork membership and its mission and vision of promoting a technology ecosystem grounded in the enjoyment of human rights, is deeply committed to engaging with workers and workers’ associations, as well as maintaining dialogue with private platforms to improve the working conditions of platform workers in Paraguay and to support the development of the local digital economy. The Fairwork Paraguay team remains available for constructive conversations aimed at enhancing transparency and platform labour standards.

1According to the Global Living Wage Coalition (GLWC), a living wage is a remuneration received for a standard work week by a worker in a particular place sufficient to afford a decent standard of living for the worker and her or his family.

ABC of our community in 2023

ABC of our community in 2023  TEDIC in the Media in 2025

TEDIC in the Media in 2025